Turkish politics has long been a subject of intense academic interest due to its dynamic

atmosphere and often turbulent nature. The importance of Turkey’s geopolitical location,

which serves as a bridge between the east and the west, has also increased the interest in

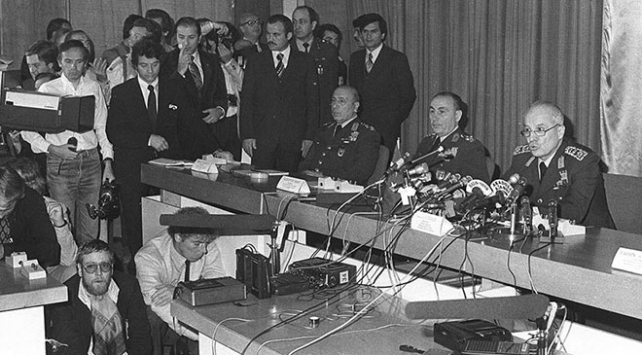

Turkish politics. The military coups, which have periodically interrupted Turkey’s political

development, serve as critical junctures that have repeatedly reshaped the political

landscape. This research aims to examine the following important question: “How did the

military coup in Turkey affect left-wing politics?” This research is not merely historical; It is

crucial to understand contemporary trends in Turkish political life and the enduring influence of the military in shaping political ideologies.

The left movement can be briefly defined as the political wing that leads the defense of the rights of the working class, the oppressed, minorities and LGBTI. Defending the rights of these social segments plays a vital role in protecting the democratic structure and advancing democracy. Assessing the impact of the 1980 military coup on the left wing movement is vital to analyze the Turkish political life for several reasons. Firstly, it offers the opportunity to understand the roots and dynamics of contemporary Turkish politics.

The coup still left permanent scars on the democratic structure of Turkish political life. It has especially harmed the democratic representation of different ideas and other ethnic groups outside the mainstream right-wing politics. Left politics, which rose rapidly in Turkish political life after the 1960 constitution and experienced heated years until 1980, was compressed into a narrow area. We can easily say that political and social structure of the left movement before and after 1980 is quite different from each other.

Historical institutionalism, the theoretical lens through which this research will be

conducted, provides a framework for examining the enduring impacts of such coups. It

posits that political outcomes are often the result of complex interactions between

institutions and the historical contexts in which they operate. Through this lens, the military

coups in Turkey can be understood not as isolated incidents but as institutional responses to perceived threats, with long-lasting effects on the trajectory of left-wing political entities.

In exploring the influence of military coups on left-wing politics, this paper will shed light on the mechanisms through which institutions constrain or enable political ideologies. It will

contribute to a deeper understanding of the ways in which political power is exercised and

contested in Turkey and will offer insights that extend beyond the Turkish case, informing

broader debates about the military’s role in political development and the resilience of leftwing politics in the face of authoritarian challenges.

In addressing this complex interplay of historical events and institutional practices, this

paper will navigate through a rich tapestry of political ideologies, state imperatives, and the

relentless pursuit of power and ideology. By examining the effects of military coups on leftwing politics, we aim to contribute to the rich narrative of Turkish political history and

provide a nuanced understanding of the enduring legacy of military intervention in political

affairs.

The connection of military coups and political ideology in Turkey has long been a pivotal

arena for scholarly debate, with a focus on the recursive influence between military

interventions and the evolution of left-wing politics. The foundational work by Ersöz

emphasizing the military’s role in rearticulating right Kemalist nationalist ideas, setting a

stage for perennial guardianship over Turkish politics. (Akar, 2010) The tutelage role of the

military on politics in Turkey’s political life has been a long-term debate. Here, the military

forces tried to suppress the leftist movements they saw as a threat, under the pretext of

protecting the constitutional order and ensuring public security.

In these studies, it was stated that the military resorted to violent suppression of leftist

movements, which became increasingly stronger after 1970, as they saw them as a threat to their own economic, political and social interests. The study of Yılmaz, who argues that the 1980 coup in Turkey reshaped political alliances and party structures, has an important place here. (Yılmaz, 2005) According to some studies the post-coup eras, especially after 1980, signaled a nadir for left-wing ideologies, with stringent censorship and persecution leading to a fragmentation of leftist groups. This assertion is underlined by Demir’s analysis of political party activities, which suggests a correlation between military coups and the

subsequent diminution of left-wing political expression in legislative bodies. (Demir, 2013)

The institutional perspectives put forward by Karadeniz offer highly valid insights into the

permanent structural changes caused by military coups. Karadeniz argues that the military’s incursions into the political sphere gave rise to institutional legacies that persistently shaped the operational paradigms of left-wing movement. (Karadeniz, 2018) This viewpoint is criticized by Öztürk , who suggests that an overemphasis on institutional impacts neglects the interstitial spaces within which political actors negotiate power and resistance. (Öztürk, 2019) However my view here is closer to the Karadeniz’s view. Military tutelage in the period after the 1980 coup; It has taken a number of important institutional changes to suppress labor movements, union movements, workers’ rights and wages, and the right to strike.

Studies in the existing literature often neglect an institutional and systematic examination of the processes by which military coups recalibrate the spectrum of left-wing politics. This gap underscores the need for an in-depth process tracing methodology that illuminates the

sequential and contingent interactions between military actions and political responses.

Building on the theoretical scaffolding of historical institutionalism, this study aims to fill this gap by tracing the complex causal pathways that determine the trajectory of left politics in the shadow of military interventions.

Historical Institutionalism assumes that actors are influenced by historical legacies and

institutional constraints. The motivations behind restrictions on union and workers’ rights

can be understood from the perspective of the post-coup consolidation of power and the

imposition of a certain socio-political order. Historical institutionalism considers concepts

such as power dynamics, path dependency, and institutional changes when examining the

effects of the 1980 Turkish military coup. They play an important role in understanding the

concrete applications of these concepts in the Turkish case and the effects of the coup on

left-wing politics.

The 1980 Turkish military coup left deep and permanent scars on the left movement. The

historical institutionalism perspective highlights concepts such as power dynamics, path

dependency and institutional changes when analyzing the effects of this turning point on left movements. This theoretical framework helps explain how the political and social

transformations caused by the coup led to permanent structural changes and how leftist

movements were repositioned on the political scene in Turkey.

Power Dynamics and Left Movements

The 1980 coup sharply changed the power dynamics in Turkey. The military and its elite

supporters took control of the state and became a dominant force in the political sphere. In

this process, left movements and their political representations were suppressed and

marginalized. The banning of left-wing parties and the arrest or exile of their leaders are the most obvious indicators of this power shift. The difficulties experienced by left movements during this period caused the political space to narrow and the way left ideologies were expressed to change, Following the coup, the activities of left-wing parties such as the Workers’ Party of Turkey (TİP) were halted and their leaders were arrested or forced into exile. Journalist Uğur Mumcu described what happened after the coup as “the suspension of democracy and the intimidation of the left in Turkey” (Mumcu, 1981)

Path Dependency and Constitutional Changes

The 1982 Constitution is at the center of the constitutional and institutional changes made

in the post-coup period. This new constitutional framework increased control over freedom

of expression and association by placing strict restrictions on the activities of political

parties. The strict regulations brought by the Constitution led to the determination of a new

path in Turkey’s political development, and this path included difficulties and restrictions,

especially for left-wing movements. The concept of path dependency explains that the

decisions taken and changes made during this period created long-term effects on Turkey’s

political and social development. Political scientist Ergun Özbudun stated that “the 1982

Constitution hindered democratization efforts and narrowed the political space” (Özbudun,

1987)

The Impact of Institutional Changes on Left Movements

The institutional changes made after the coup directly affected the activities and

organizational forms of left movements. Restrictions on areas of social and political

organization such as universities and unions weakened the left’s social base and limited its

political effectiveness. These transformations necessitated the restructuring of left

movements and led to permanent changes in the ways left ideologies are expressed and

represented in Turkey’s political landscape. Here my hypothesis is that many institutional

changes that took place with the 1980 military coup caused the left movement to differ

considerably compared to before the coup.

The 1982 Constitution imposed significant restrictions on freedom of expression and

assembly. In particular, Article 28 contains provisions limiting freedom of expression to

broad concepts such as “national security, public order, public safety, public morals and

health”. This has restricted left-wing political parties and movements from expressing their

activities in the public sphere and in the media. Restrictions on the Activities of Political

Parties: Article 68 of the Constitution regulates the establishment and activities of political

parties and prohibits activities that “will endanger the independence and integrity of the

state, national sovereignty and the republic”. These provisions allowed the pressure on leftwing parties to be carried out on a legal basis. Limitation of Trade Union Rights: While Article 51 of the Constitution contains regulations on trade union rights, it contains provisions that may limit the use of these rights in line with general interests such as “national security, public order or prevention of crime”. This facilitated control over labor movements and leftwing union activities. Restriction of the Autonomy of Universities: Articles 130 and 131 of the 1982 Constitution brought regulations regarding the management of higher education institutions and enabled the establishment of the Council of Higher Education (YÖK).

This regulation limited the autonomy of universities, increased state control over academic

freedoms, and suppressed left-wing academics and student movements. (Tanör &

Yüzbaşıoğlu, 2023)

This theory section aims to comprehensively examine the lasting effects of the political and

institutional transformations caused by the coup on left politics by addressing the effects of

the 1980 Turkish military coup on left movements from the perspective of historical

institutionalism. The effects of the coup on left-wing movements should be considered as a

turning point in Turkey’s political history, and the long-term consequences of these

transformations on political development should be carefully analyzed. This article adopts

historical institutionalism to illuminate the lasting impact of the 1980 military coup on leftwing politics in Turkey. By focusing on the temporal continuity and transformative power of political events, historical institutionalism provides an analytical lens for examining longterm political changes in left movements initiated by the military’s intervention in civilian rule.

Process tracing within the framework of historical institutionalism emerges as the

methodological backbone of this analysis. Process tracing will allow meticulous examination

of the causal mechanisms and sequences underlying the impact of the 1980 military coup on the political trajectory of the left movement in Turkey. Process tracing serves as a tool in

political science, dissecting complex events to reveal the hidden anatomy of causation. The

strength of process tracing in exploring such complex social and political phenomena lies in

its attention to detail. It doesn’t just look at before-and-after scenarios; it considers the

entire spectrum of events, decisions, and responses that connect cause and effect.

This study, through process tracking, deals with the change of leftist movements that began to become increasingly prominent in the public sphere after the 1961 constitution, one of the most democratic constitutions of Turkey, gradually increased it’s popularity with the 1970s, became stronger, and then it experienced the shock effect after the 1980 military coup. This study, through process tracking, deals with the changes experienced by leftist movements that began to become increasingly prominent in the public sphere after the 1961 constitution, one of the most democratic constitutions of Turkey, gradually increased in popularity with the 1970s, became much more stronger, and then the shock effects with the 1980 military coup. We can easily say that after the 1980 coup, the left movement lost its popularity, vitality and power before the coup. Left-wing movements have gone down the path of making alliances with right-wing, nationalist groups that are completely different from their worldview in order to expand their sphere of influence. This led to the differentiation, division and even marginalization of leftist movements over time.

The justification for this design lies in its ability to illuminate the causal pathways and

institutional changes that are hypothesized to have systematically marginalized, fragmented, or transformed the left-wing political entities in Turkey.

It is possible to see other examples other than Turkey where military coups disrupted left

movements. In examples such as Chile and Greece, unfortunately, institutional changes

made as a result of military coups have degraded workers’ rights, restricted union rights, and prevented the rights of assembly and demonstration. Restriction of these rights, which

constitute the organizational forms of left movements, has set back the left movements in

these countries. Here, it will be important to benefit from similar examples in different

countries in order to understand comparatively the evolution of the left movement in Turkey after the coup. The principal assumption undergirding this design is the integrity and accessibility of historical records, various articles which is crucial for establishing the causal links between military interventions and political changes. However, one of the most difficult assumptions to test is the counterfactual scenario: What would the course of left-wing politics in Turkey be like if there were no military interventions? Although the study may speculate on alternative paths based on comparative analysis, the actual situation of a coupfree Turkish political landscape remains hypothetical. In conclusion, the research design combining historical institutionalism with process tracing provides a solid framework for investigating the profound question at the heart of this study, namely how military coups shaped the contours and fate of left-wing politics in Turkey. This analysis aims to contribute significantly to the study of Turkish political history and broader discourses on the dynamics between military power and political ideologies by revealing the institutional legacies and causal processes that drive political ideologies.

The data to be used in this article will be articles, statements of politicians, and a series of

academic studies in this field. Especially in the 1970s, there were an increasing number of

assassinations and street clashes between right and left movements. Here, the right

movement was attacking members of the left movement, with the support of some organs

of the state and the counter-guerrilla (gladio) structure. Despite all, the left movement

continued to grow stronger in the 1970s, organize workers and strengthen union rights.

Realizing that their own interest mechanisms were increasingly being questioned as a result

of this process, some military groups within the state realized that this issue could not be

solved by just supporting far-right extremists in the street conflicts. In the following period,

the September 12 coup took place. Here, we can understand the cooperation of extreme

right-wingers and the military/state mechanism to suppress the left movement, by using the words spoken by the politicians of that period as a source. Agah Oktay Güner, who served as the minister of commerce before the 1980 coup and was also the deputy chairman of the nationalist movement party, made this cooperation very clear by saying “Our ideas are in power, but we are in prison” in the case he tried after the coup. (Türk Yurdu, 2010)

After the coup, the left movement lost much of its power. Their right to engage in politics in

a legitimate and democratic political environment was taken away from them, and as a

result, they were pushed to marginalization. After the coup, economic liberalism decisions

called January 24 decisions were implemented. Workers’ rights have completely declined.

The unionization rate of workers has decreased. In the post-coup elections, the votes of leftwing parties dropped significantly compared to the pre-coup period. We can analyze what I have said by examining data such as unionization rates and left party votes before and after the coup. (Göçek, 1987) While the unionization rate was approximately 40 percent in 1980, it fell below 14 percent after the coup period. After the September 12 coup, lockout and strike bans were included in the constitution, rights strikes were banned, and unions were banned from engaging in politics. This conclusion can be reached by examining the documents containing the 1981 constitution and laws.

The basic assumption is that the military coup had a direct impact on left-wing politics. After the coup, the left movement lost much of its power and was confined to a narrow area. This assumes a causal relationship in which the coup is an independent variable that directly affects the dependent variable, which is the state of left politics. We need also to examine the issue of Stability of Other Variables. Another assumption is that other external variables, such as international political pressures or economic conditions, remained relatively constant over the period of the study or did not change in a way that would significantly affect left-wing politics. Because at the time of the coup, the cold war was still going on and the Soviet Union still did not collapse. This is to ensure that changes in left-wing politics can be attributed to the coup rather than other factors.

The basic assumption is that the military coup had a direct impact on left-wing politics. After the coup, the left movement lost much of its power and was confined to a narrow area. This assumes a causal relationship in which the coup is an independent variable that directly affects the dependent variable, which is the state of left politics.

We need to examine the issue of Stability of Other Variables: Another assumption is that

other external variables, such as international political pressures or economic conditions,

remained relatively constant over the period of the study or did not change in a way that

would significantly affect left-wing politics. Because at the time of the coup, the cold war

was still going on and the Soviet Union still did not collapse. This is to ensure that changes in left-wing politics can be attributed to the coup rather than other factors. As for the integrity of the data. The assumption here is that the data collected for the period are accurate, reliable and sufficient to represent the actual political climate and events of the period.

Numerical data on union membership before and after the coup, vote rates of left-wing

parties, legal amendments and the coup constitution are quite clear and can be examined.

A specific assumption that could not be tested for my research question would be the

assumption that the leaders of the military coup specifically aimed to reduce the influence

of left-wing politics in Turkey. This assumption is difficult to test empirically because it

requires access to coup leaders’ internal motivations and intentions, which are subjective

and not always documented or clearly expressed in the historical record.

This research, based on historical institutionalism and meticulously conducted through

process tracing, illuminated the complex dynamics that emerged after the military coup in

Turkey and its profound effects on left-wing movements. By delving into the historical

sequences and critical junctures precipitated by the coup, we reveal the layered and often

subtle mechanisms through which military interventions can recalibrate the political

landscape, especially for movements on the left of the political spectrum. Our research

reveals not only the suppression or transformation of left-wing parties, but also the longterm changes in the political strategies, discourses and alliances that these movements have had to navigate. The resilience and adaptability of left politics in the face of systemic

challenges and constraints underscores the complex interplay between political institutions

and ideologies. Moreover, the nuanced understanding gained from this analysis highlights

the critical role of historical legacies and path dependencies in shaping political outcomes

and challenges us to consider how past events continue to cast long shadows on current and future political configurations.

More importantly, this study serves as a reminder of the value of integrating rigorous

theoretical frameworks with comprehensive empirical analysis to examine complex sociopolitical phenomena. While historical institutionalism provided a lens through which to view the lasting impact of the coup, process tracing enabled detailed examination of the causal pathways and mechanisms at work. We can easily say that the left movement, which has been on the rise since the 1960s, had a questioning angle towards the system by taking workers, laborers, intellectuals and students with it. Thereupon, the gradual increase in workers’, laborers’ and union rights’ rights also made the capitalists uneasy.

For this reason, the military, which described itself as the protector of the status quo, carried out a coup in 1980. After this coup, workers’ rights and union rights gradually declined. The left movement was fragmented and therefore gradually weakened. In order to get involved in politics, they were forced to cooperate with right-wing political movements. These political collaborations caused divisions in left movements and a gradual decrease in their votes. However, the restriction of constitutional rights such as demonstration and protest has also narrowed the field of organization of left movements.

References

Akar, A. (2010). The Twilight of Leftist Ideals: The Impact of Military Coup on Turkish Politics.

Ankara University Press.

Demir, O. (2013). Legislative Dynamics in Post Coup Turkey: An Emprical Study. Boğaziçi

University Press.

Göçek, F. M. (1987). State versus people: A study of military intervention in Turkey. Middle

East Journal, 351-368.

Karadeniz, M. (2018). Institutional Legacies and Political Continuity: An Analysis of Turkey’s

Coup D’etat. Journal of Turkish Political Studies.

Mumcu, U. (1981). 12 Eylül: Silahlı Demokrasi. Tekin Yayınevi.

Özbudun, E. (1987). The constitutional System of Turkey: 1876 to the present. Palgrave

Macmillan.

Öztürk, S. (2019). Beyond Institutions : Agency and Power in Turkish Political Life. Journal of

Middle Eastern Politics.

Tanör, B., & Yüzbaşıoğlu, N. (2023). türk anayasa hukuku. beta.

Türk Yurdu. (2010).

Yılmaz, D. (2005). Interrupted Paths: Military Coups and Political Parties in Turkey. Middle

East Technical University Press.

Sinema

Sinema Tarih

Tarih Spor

Spor Moda

Moda Röportajlar

Röportajlar Ekonomi

Ekonomi Oyun

Oyun Bilgi

Bilgi Covid-19

Covid-19